Most people will tell you that it’s insanity to change machines and editing platforms in the middle of a feature film project, right? But that’s exactly what I just did. And I think it’s going to make all the difference.

I’ve been editing the film on a Mac Book Pro that I bought in 2009 or 2010. It was a state-of-the-art machine at the time, with a 2.8 GHz Intel Core 2 Duo with 4 GB of RAM. I was running Final Cut Studio 3, which includes Final Cut Pro 7. But Multi-Cam never actually worked (which is a pain when you have up to four cameras per aircraft) and the spinning beach ball of death (“SBBOD”) or the slowly-crawling render bar spent more time on my screen than is conducive to the creative process.

So I finally decided to drop money I don’t have on a new setup. And it turns out to have been more than worth it. The new rig is the current state-of-the-art Mac Book Pro with a 15″ Retina display, additional NVIDIA processing to handle it, 2.6GHz quad-core Intel Core i7 with Turbo Boost up to 3.5GHz, 16GB of 1600MHz memory, and 512GB of PCIe-based flash storage. It screams as fast as any Mac Book available without Frankenstein mods.

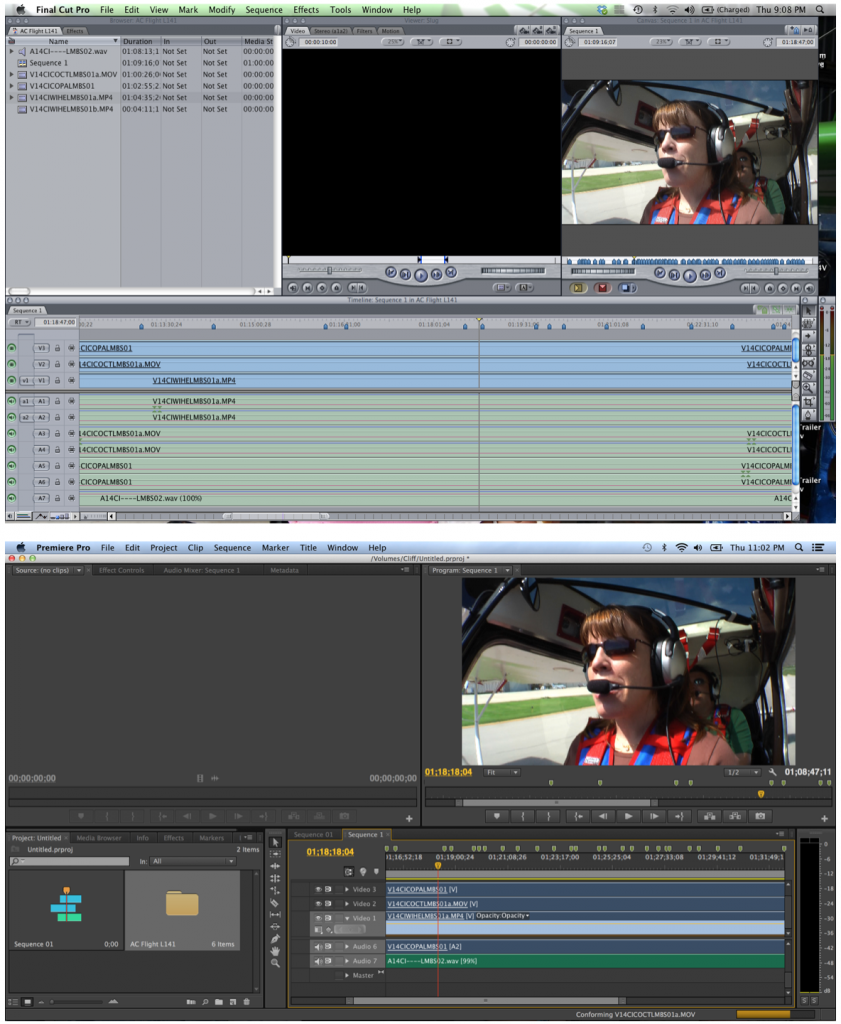

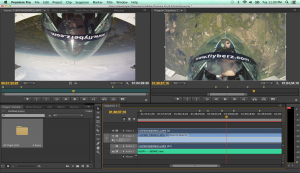

Will Hawkins, the jerk that make me think that I could make a movie in the first place (love you, man!), talked me into getting Adobe Premiere CS6 and migrating to it from FCP 7. He explained that one can export FCP projects as XML files and then import them with Premiere and that the process is pretty straightforward. It turns out that he was on the mark as far as I can tell. The lead image for this post shows one of the flight sequences in FCP 7 on the top and the same sequence in Adobe Premiere on the bottom. It took me 30 seconds to export the XML from FCP and another 60 seconds to import the sequence into Adobe Premiere. Nice.

The translation isn’t exact. But it’s not different in any materially adverse way that I’ve discovered yet. And I can always go out to Cali and beat Will’s head in with one his own heathen tiki gods if I find out later that there’s some massive discontinuity that I’ve missed.

Perhaps the biggest advantage of Adobe Premiere is that it displays widely differing video files (MOV from the big cameras, M4V from the GoPros, etc.) without any need to render first. I can even flip the video from the Pitts hand-hold camera 180 degrees and Premiere just displays it that way – no rendering required. This is especially important when you’re trying to align someone’s lips with the cockpit audio track and you need smooth video to do it and you don’t want to wait 20 minutes to render enough of it to start making intelligent guesses. (And then render more of it when you guessed wrong.) Even if there are discontinuities and I have to develop different workflows, the time that I save rendering and the maintenance of creative momentum might save Will. And his heathen tiki god.

So here’s what’s up going forward. I’ve already made XML files out of all of the sequences that I think I’m going to need and tried out a few. Next, I’ll probably put together a few clips to toss out on Facebook and otherwise so people can see that stuff is moving forward. After that, I’ll import all of the other sequences and begin putting together pieces of the movie.

Concurrently with that last piece, I need to reserve a weekend and take over the board room at the office and spread out all of the film logs and make some decisions about larger sequences, the overall organization of the film, and what’s going to go where. I can also start writing some of the narration and figure out what connective tissue I’m going to need.

The new hardware and software were a bullet that I didn’t want to have to bite, but I can already see that they’re essential to the way forward. Being able to play with the sequences will be essential going forward and I have the tools to really move forward with that process.